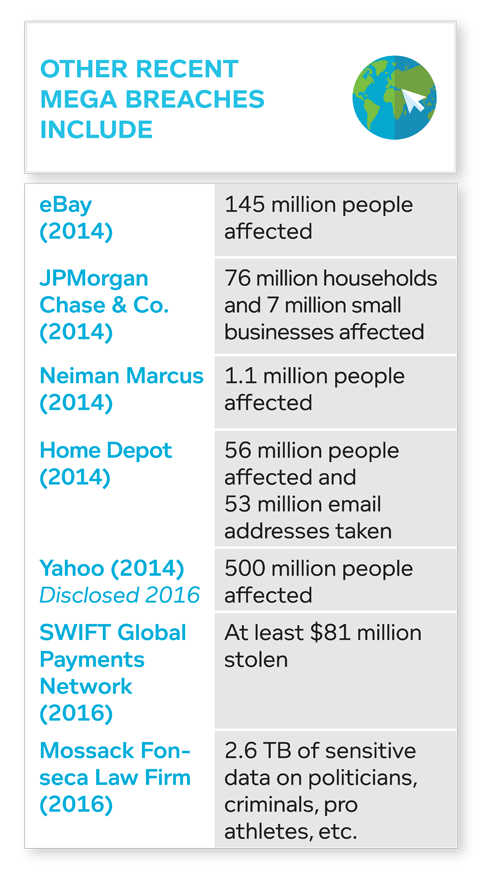

Where there is data, there is the potential for data loss. How an organization prepares for and manages a data incident will have a measurable impact on the outcome. A data incident that could potentially cost millions of dollars and shatter an organization’s reputation can, if handled effectively, be brought under control and have a significantly reduced impact. For instance, following a well-publicized data breach involving malware installed on Home Depot’s self-checkout kiosks, two Canadian firms launched class action lawsuits seeking $500 million; the lawsuits ultimately settled for $400,000. The significant reduction was warranted, said the judge, because of Home Depot’s “exemplary” response:1

In the immediate case, given that: (a) Home Depot apparently did nothing wrong; (b) it responded in a responsible, prompt, generous, and exemplary fashion to the criminal acts perpetrated on it by the computer hackers; (c) Home Depot needed no behaviour management; (d) the Class Members’ likelihood of success against Home Depot both on liability and on proof of any consequent damages was in the range of negligible to remote; and (e) the risk and expense of failure in the litigation were correspondingly substantial and proximate, I would have approved a discontinuance of Mr. Lozanski’s proposed class action with or without costs and without any benefits achieved by the putative Class Members.

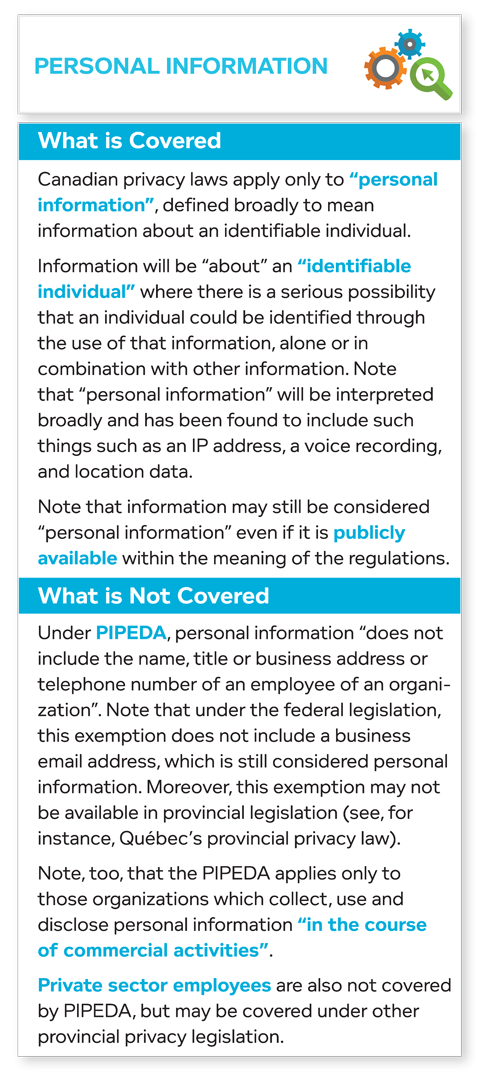

Data that can be used to identify an individual constitutes personal information, and the collection of this kind of data creates privacy obligations (and triggers privacy laws). With advances in technology, organizations are collecting, storing and transferring more personal information about their consumers, professionals, patients and employees than ever before. The accumulation of vast amounts of personal information in large databases increases both the risk and impact of unauthorized access to that information. A single data incident involving personal information can now affect millions of individuals.

With biometric identifiers (e.g. fingerprints, voice prints, facial recognition) increasingly being adopted by businesses, there are now new risks created by the loss or misuse of these immutable identifiers.

While data incidents continue to grow in size, the more notable development in is the increasing sophistication of those behind such incidents. The perpetrators’ business models have evolved and an addition to using more complex methods, their targets have shifted. Whereas once the modus operandi was to steal credit card information and use it for unauthorized transactions, increasingly malicious actors are relying on social engineering methods (e.g. phishing – fraudulent emails used to dupe unsuspecting employees into provide confidential or sensitive information) to gain access to information of value to the company. This is information is then monetized directly by using it for insider trading, selling it to competitors (in the case of intellectual property or trade secrets), or demanding a ransom for its return.

Senior managements’ concern about a data incident has risen dramatically and it has become accepted wisdom that companies should not be asking if a data incident will occur, but when.

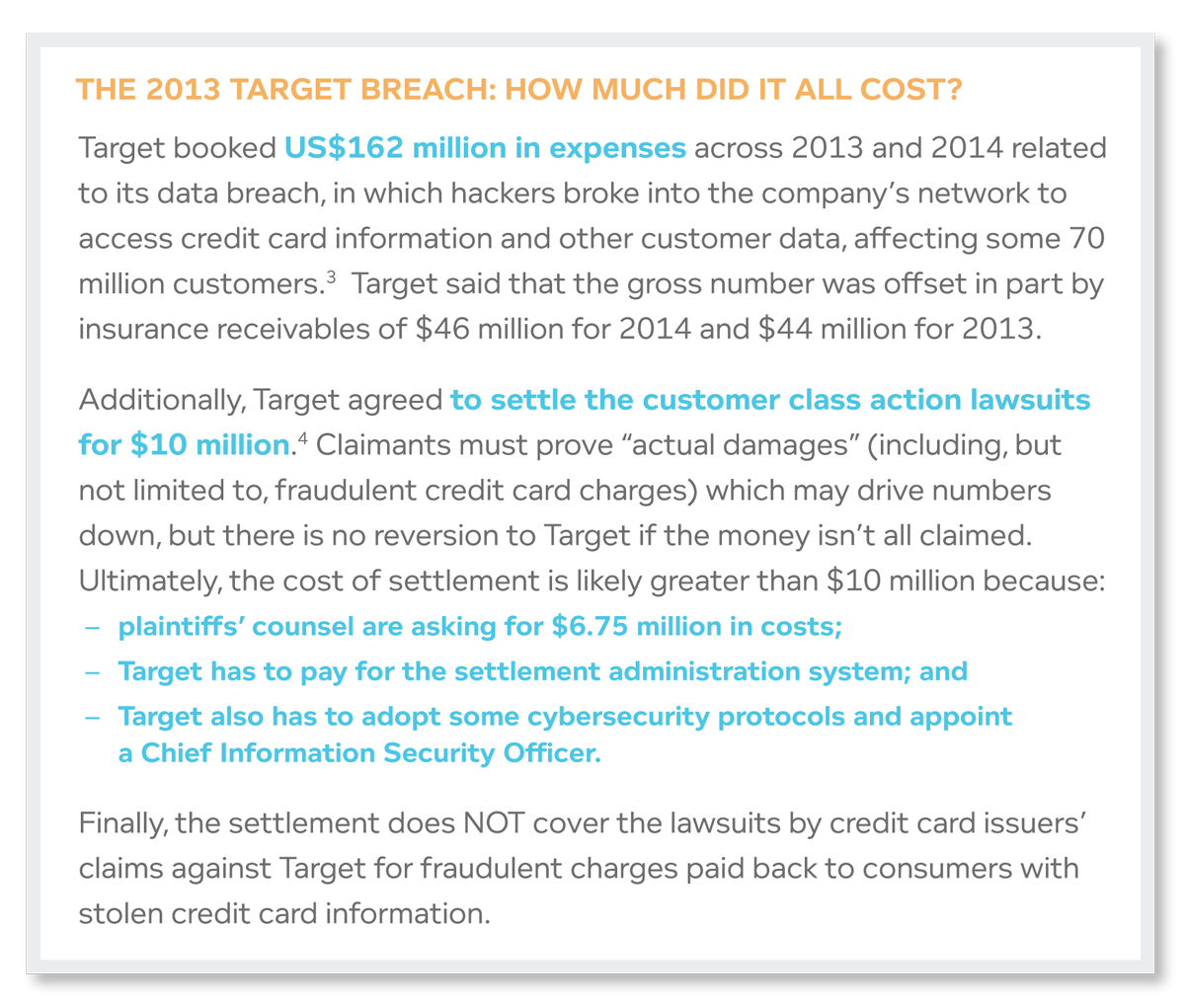

Data incidents are becoming increasingly expensive. While new products (such as cybersecurity risk insurance) are available to help defray costs, litigation (especially class action litigation) is now the expected response to a report of a data incident. While damage awards have to date been relatively small, the cost of managing a data incident can be shockingly high.

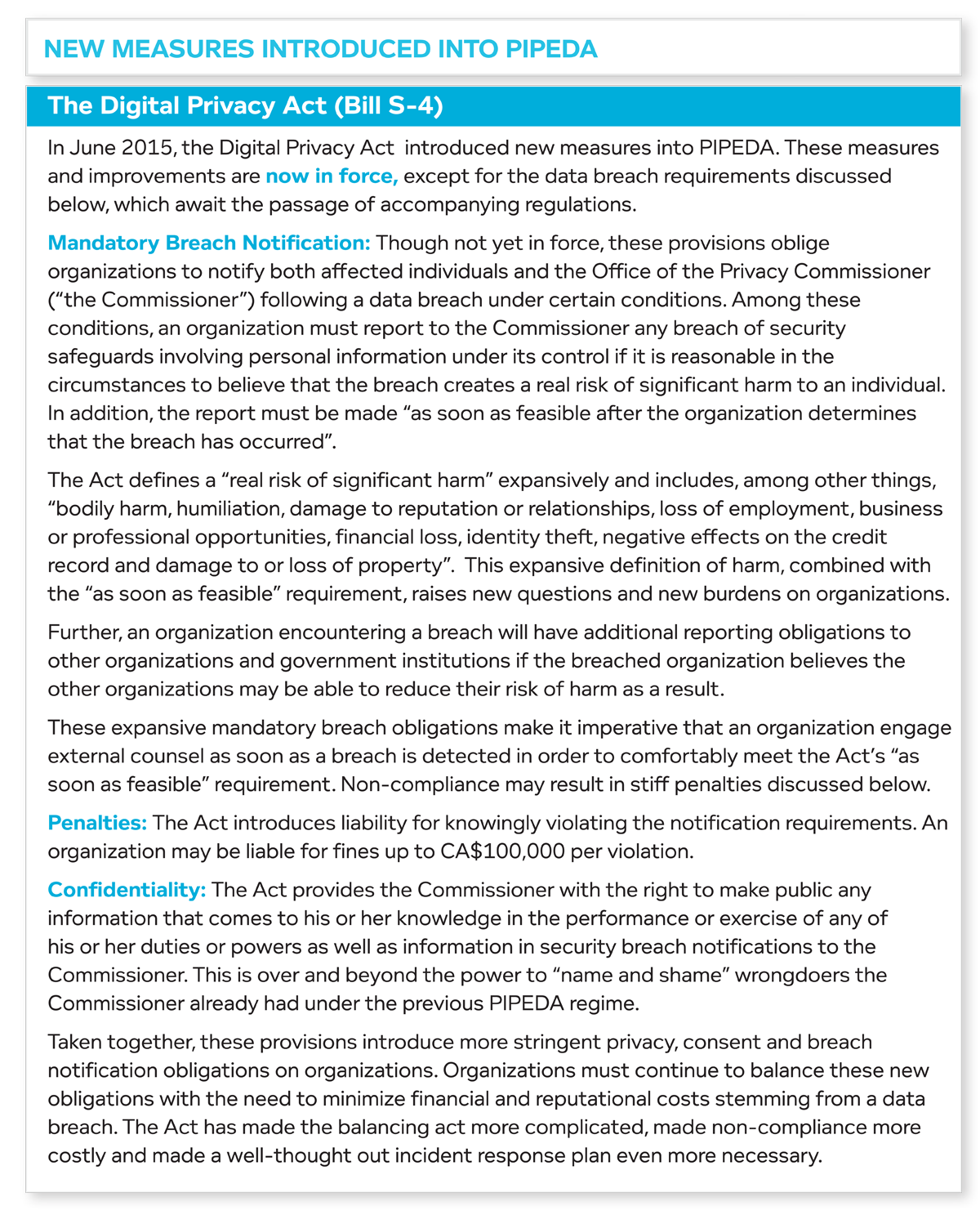

There are significant regulatory costs. Recent amendments to Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), introduced mandatory breach notification and penalties of CA$100,000 per violation for non-compliance with this requirement, further increasing the financial and reputational costs related to data incidents.

The costs don’t end with damages – accountability for data incidents can reach into the boardroom. Gregg Steinhafel, Target’s CEO and chair of the board, resigned shortly after that company’s data incident.2 A similar fate befell Amy Pascal, who stepped down as head of Sony Pictures in the wake of the Sony hack.

First 72 hours are critical. While not all data incidents are of headline-grabbing magnitude, the worst incursion can throw an entire organization into turmoil for months on end. The first 72 hours after a data incident are, in particular, a chaotic mix of moving parts, most of which have to be addressed simultaneously, using information which is not yet complete.

A cybersecurity incident response plan prepared in advance for a trained and tested incident response team goes a long way towards staving off the chaos, keeps key players on-message, and focuses the efforts of the team on identified priorities. Importantly, an incident response plan lends structure to the urgent work and can be an important brake on unfocused activity and the urge to “do something”. Moreover, a tightly scripted response reduces costs, reduces the over-involvement of outside vendors, helps preserve evidence that may establish that the organization met the applicable standard of care, and minimizes reputational damage.

A properly designed, documented, and executed plan is critical to limiting data loss and organizational disruption. More importantly, it will assist in minimizing liability to third parties and to regulators provided it is regularly updated to reflect changes in cybersecurity awareness.

An organization, if sued, will ultimately have its incident response plan (and its implementation thereof) evaluated by a court against a standard of reasonableness. With new risks and threats (and responses and patches) being identified every week, an incident response plan cannot be a static document. A court charged with evaluating the reasonableness of an incident response plan will look not only at the paper documents that an organization relies on but, among other things, whether policies were followed, whether appropriate technical, financial and employee resources were allocated, and whether senior management was involved in the creation and management of the plan.

The standard of care may also be evaluated against regulatory guidance in specific sectors. For instance, on September 27, 2016 the Canadian Securities Administrators (“CSA”) issued CSA Staff Notice 11-332 – Cyber Security (“2016 Notice”) and stated that, in its view, it is no longer sufficient for regulated entities to merely put in place a reactive “breach response plan”. What is required, according to the CSA, is a proactive “cybersecurity framework” to better manage and reduce cybersecurity risk. A “cybersecurity framework”, according to the CSA, consists of “a complete set of organizational resources, including policies, staff, processes, practices and technologies used to assess and mitigate cyber risks and attacks." (see further discussion of the 2016 Notice in the section on Public Company Risk Disclosure, below).

Previously viewed as an unwieldy compliance effort that saw little in the way of return on investment, savvy companies are beginning to realize that enhanced data protection and a robust incident response can be a competitive advantage. A 2015 research survey showed that 25 percent of respondents believe their organization’s C-level views security as a competitive advantage.5 More tellingly, 59 percent of respondents say C-level executives will view security as a competitive advantage by 2018.

While a data incident may seem almost inevitable, it need not be a catastrophe. Organizations which are prepared to handle an incident, and integrate incident preparedness and prevention into their overall cybersecurity risk management program, are significantly more likely to have favourable outcomes in the event of an incident (and more likely to avoid an incident altogether) than those organizations which adopt an ad hoc approach. In the context of a breach, a “more favourable outcome” includes an incident resolution process that attracts limited media attention, minimizes costs (particularly costs associated with the threat of litigation), limits reputational impact, streamlines stakeholder involvement and invites minimal scrutiny from regulators.

A cybersecurity program consists of a cybersecurity framework, along with a cybersecurity incident response plan. A cybersecurity framework is proactive, and is a complete set of organizational resources, including policies, staff, processes, practices and technologies used to assess and mitigate cyber risks and attacks. A cybersecurity incident response plan is reactive, and is an enterprise-wide undertaking that provides a protocol for the entire organization, assigns accountabilities and sets up metrics to track organizational efforts to resolve the incident. It includes a variety of specific elements and covers a wide range of disciplines. Importantly, it is comprehensive and detailed, consisting of more than check boxes and To Do lists.

Some of the key elements of a cybersecurity program are outlined below.

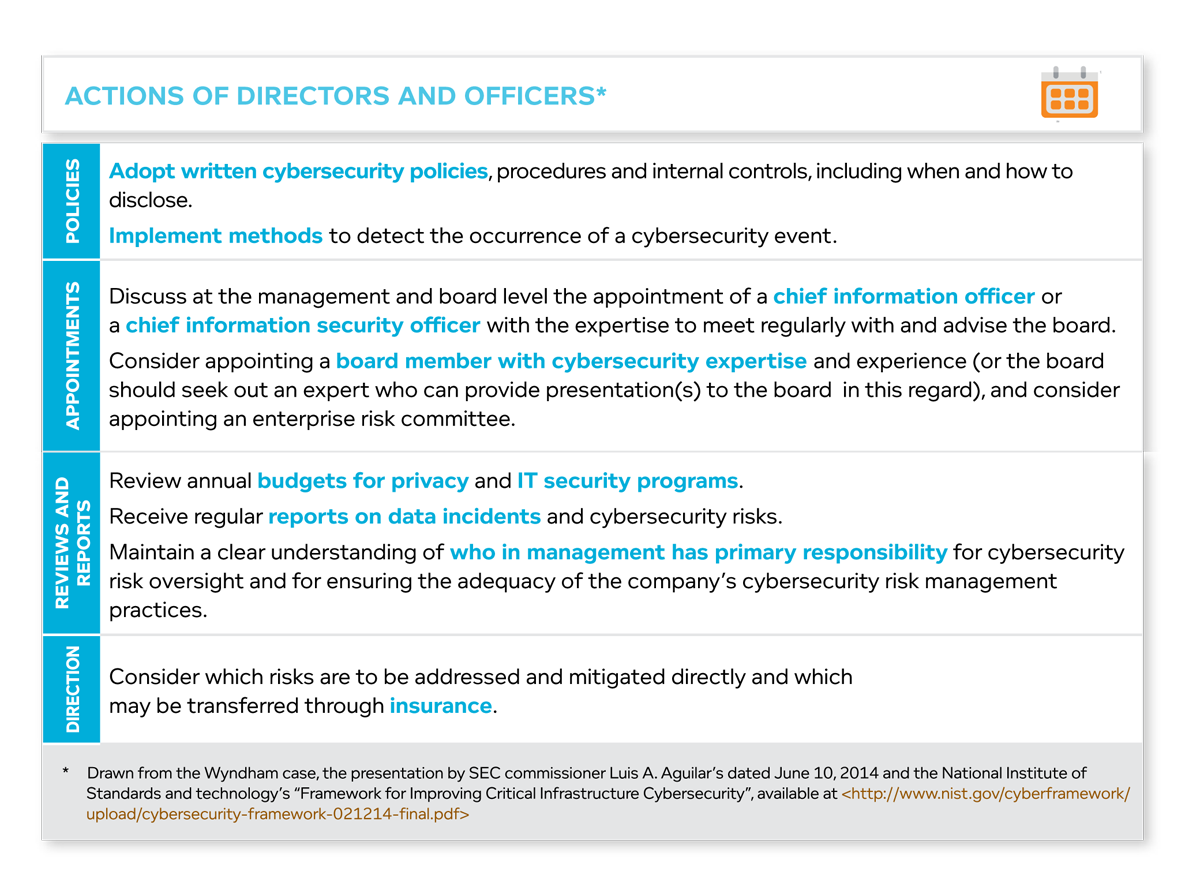

Cybersecurity is not solely an information technology risk. It is an enterprise-wide risk, and should be part of a board of directors’ general risk management mandate.

Cybersecurity needs to be addressed in the boardroom. In June 2014, SEC Commissioner Luis Aguilar spoke to the New York Stock Exchange about cybersecurity risks in the boardroom, noting that cybersecurity incidents have become more frequent and sophisticated, but they have also become more costly to companies.6 He emphasized that, in light of this, the role of boards of directors, noting that “ensuring the adequacy of a company’s cybersecurity measures needs to be a critical part of a board of director’s risk oversight responsibilities.”

Regulators are beginning to move away from voluntary compliance. On September 13, 2016, the New York State Department of Financial Services (“DFS”) announced a proposed new cybersecurity regulation (the “Regulation”) that will apply to banks, insurance companies, and other financial services institutions regulated by the DFS. The Regulation is intended to protect both the information technology systems of regulated entities and the non-public customer information they hold from the growing threat of cyberattack and cyber-infiltration. Among other things, the Regulation requires action in four key areas: (a) establishing a cybersecurity program; (b) establishing a cybersecurity policy; (c) designating a Chief Information Security Officer; and (d) reporting and records requirements.

The Canadian approach, to date, has been somewhat different. While no Canadian jurisdiction to date has passed any similar regulation, the CSA issued its 2016 Notice noting the failure of many issuers to fully disclose their exposure to cyber risks and indicating they intend to re-examine the disclosure of some of the larger issuers. (For more on this, see the section on Public Company Risk Disclosure below.)

Courts have also begun to consider the role of directors in considering cybersecurity risk. On October 20, 2014, a New Jersey Court dismissed a shareholder derivative suit that sought damages notably from the directors and officers of Wyndham Worldwide Corp. for several data breaches.7 This decision was the first decision issued in the United States in a shareholder derivative claim arising out of a data incident. Similar lawsuits were filed in the District of Minnesota against the directors and officers of Target. These lawsuits named 13 of Target’s directors and officers as defendants and asserted claims for breach of fiduciary duty and waste of corporate assets, among others. The shareholders challenged not only the directors’ and officers’ conduct before the data breach by alleging their misconduct allowed the data breach to happen, but also challenged their conduct following discovery of the data breach by asserting the directors and officers acted improperly in the way they disclosed, investigated, and remediated the data breach. These lawsuits were also dismissed.8

These decisions provide examples of approaches to cyber risk oversight that directors and officers may implement to help shield them from liability in the context of data incident.

In light of the decision rendered in the Wyndham case, the following are examples of steps that could be considered by management and boards of directors in identifying and assessing an organization’s cybersecurity risks.

A key element of cybersecurity risk management program will be an organization’s policies and procedures. While the content of policies may vary, there are certain common elements. For instance, no matter what the specific policies are, are they written in plain English and understandable by all levels of employees? Are they easily accessible (e.g. available on an intranet)? Do employees receive formal training?

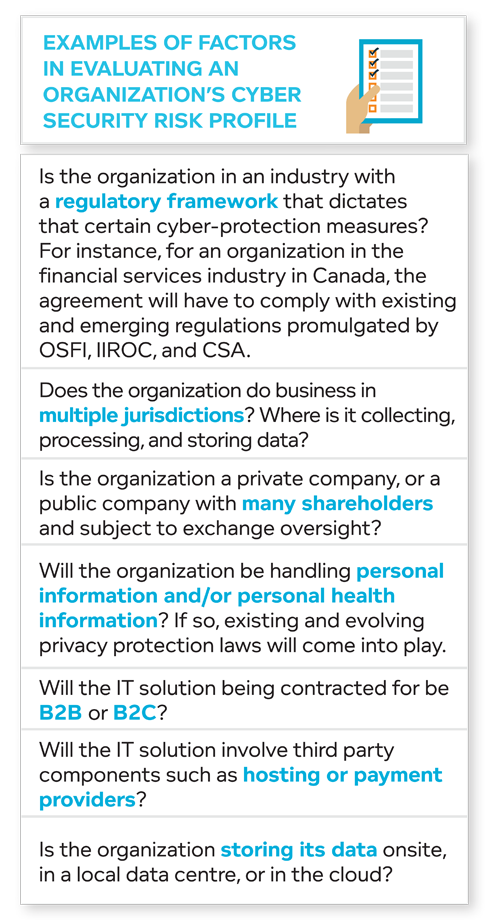

The specific components of any program will vary from organization to organization depending upon jurisdiction, industry and an organization’s risk tolerance.

Some specific areas for training and policies may include the following:

Does the organization have materials and training that provide guidance to the information security team? Items that such a policy might include are:

In the event of a data incident, an organization’s policies will likely be requested by the regulator and, if the organization has been sued, plaintiff’s counsel. As a result, counsel should review all policies prior to finalization.

The most basic form of access control is user privileges, which refers to the right or rights a user has to access company systems and data. The prevailing principle is that of “least privileges”, which dictates that users be granted only the level of access necessary for them to do their job.

This principle applies not only to employees, but also to vendors and other third parties. In many cases, these types of relationships will be governed by contracts, which can also become a key element of cybersecurity preparedness, with contract provisions geared towards prevention, response, mitigation, and remedy.

There are two general scenarios, the first where an organization is contracting with a vendor for actual IT services, the second is where organization is contracting with a vendor for some other product or service which requires access to the IT system (e.g. a lighting services supplier who needs access to an organization’s IT systems for environmental monitoring). While both require cybersecurity due diligence, the due diligence considerations go much deeper for the first scenario.

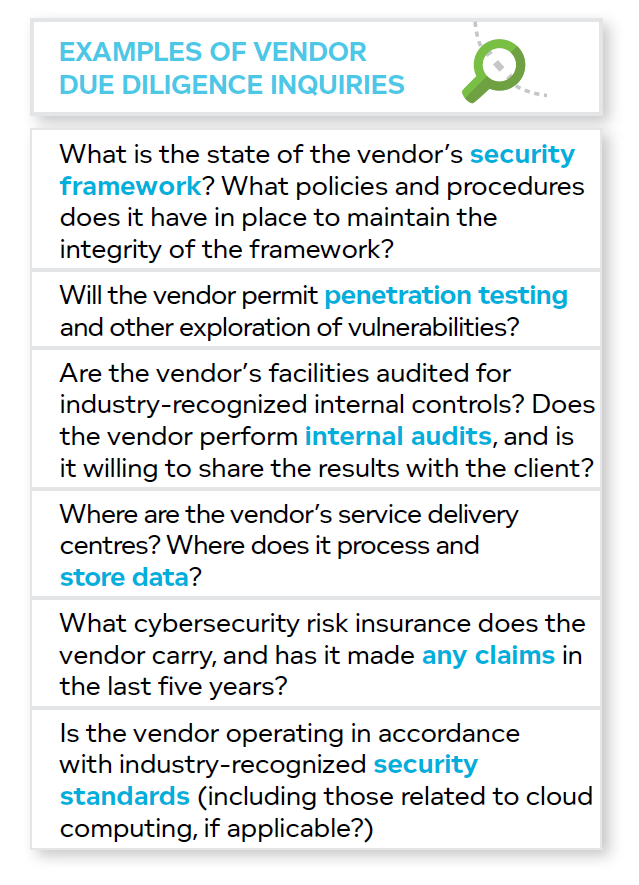

For an IT services agreement, the starting point will be to understand the organization’s cybersecurity risks (see sidebar).

In addition, doing proper due diligence on the vendor is an essential part of getting a best of breed contract in place. The structure and components of the vendor’s solution, and the vendor’s capabilities and certifications, risk management practices, and financial wherewithal are all elements that should be explored (see sidebar).

Then, having established the organization’s cybersecurity risk profile, and having completed thorough due diligence of the vendor, the legal team will now be in a position to tailor the various data incident prevention, response, mitigation, and remedy provisions of the proposed IT services agreement.

Some of the most important provisions in the agreement will pertain to risk allocation. The interplay of representations, warranties, indemnities and liability is generally hotly contested in the area of cybersecurity because jurisprudence is evolving. An organization may want to consult outside counsel with expertise in this area to determine how it wishes to effectively address these issues and to discuss the various avenues available.

Some of the most important provisions in the agreement will pertain to risk allocation. The interplay of representations, warranties, indemnities and liability is generally hotly contested in the area of cybersecurity because jurisprudence is evolving. An organization may want to consult outside counsel with expertise in this area to determine how it wishes to effectively address these issues and to discuss the various avenues available.

Critical to managing risk will be the organization’s IT defences – are they adequate, up to date, and informed by identified threats? It will be important for an organization to subscribe to a comprehensive and legitimate threat assessment service (for instance, Canadian Cyber Incident Response Centre (CCIRC) Cybersecurity Bulletins and best practice documents).9 There are also industry and sector groups that are engaged in information sharing. For instance, the Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures has published a report on the current cybersecurity practices of financial institutions.10

The Bank of Canada has adopted the general risk-management guidance issued by this committee as the standard for designated financial institutions, as well as calling for “[c]o-operative initiatives that facilitate information sharing enhance cyber security by creating a forum to exchange best practices, share threat-intelligence information and establish communities of trust between sectors.”11

Industry-standard antivirus and malware protection should be installed, with updates continuously installed and documented. The organization’s networks should be protected from internal and external attacks, and wireless networks should be secured using industry-standard practices, and firewalls and malware detection should be routine. Penetration testing should be conducted regularly (ideally by an independent third party). There should be technical solutions in place that detect and block suspicious activities or access.

Social engineering attacks should also be considered, and organizations should consider training their employees on how to avoid falling victim to phishing attacks, evil twin routers (a rogue Wi-Fi access point that appears to be a legitimate one offered on the premises, but actually has been set up to eavesdrop on wireless communications; an attacker fools users into connecting a laptop or mobile phone to a tainted hotspot by posing as a legitimate provider), and USB keys that appear to have been lost but are deliberately-planted malware-infected devices.

As data incidents increase in number, scope, and impact, organizations are looking to transfer the risk associated with them. The most common way of transferring risk is by obtaining insurance policies: if the risk is insurable, the risk is transferable. Marsh Inc., a global insurance broker, said that the number of organizations that purchased cybersecurity risk insurance in the US increased by 33% from 2011 to 2012, and that cybersecurity risk insurance is currently the fastest growing area of commercial insurance in the world.12

Generally, cybersecurity risk insurance is divided into first party coverage (protecting the policyholder from direct loss) and third party coverage (protecting from third party claims).

Cybersecurity risk insurance can also cover specifically the crisis stage of a data incident. This could include any expenses related to the management of the incident, such as investigation, remedial steps, required notifications, call center set up and public relations management, credit checks for the subjects of the data, and any legal costs including fines or the costs of launching or defending a lawsuit.

All insurance policy coverage is dependent on the particular terms and conditions in the policy at issue. Organizations looking to obtain cybersecurity risk insurance should consider a number of questions, and have their policies reviewed by counsel.

Until now, the discussion as focused largely on the proactive elements of a cybersecurity plan. The other major part to a cybersecurity program is the reactive cybersecurity incident response plan.

An effective incident response plan ultimately relies on executive sponsorship. The next key step to developing an effective incident response plan is to ensure the right team is involved. An incident response plan should be enterprise-wide, and draw on the experience of key personnel from key stakeholder areas within the organization. Typically, this will include senior representatives from legal, public relations/marketing, customer care, human resources, corporate security/risk management, and IT. Ideally, it will also include pre-screened and pre-selected external advisors.

The responsibilities of the team and further details of the response plan are set out in the next section, Part IV.

Once the incident response plan is drafted, it should not sit in a drawer. Organizations should train, practice, and run simulated data incidents to develop response “muscle memory.” The best-prepared organizations routinely conduct war games to stress-test their plans, increasing managers’ awareness and fine-tuning their response capabilities. Outside counsel, with sophisticated understanding as a result of having handled dozens of data incidents, will often be invited to run the simulation, and evaluate the organization’s response.

A cybersecurity response plan should be prepared in advance, be detailed, be tested, and be well understood by those within the organization. A response plan will help focus the efforts of a diverse group of people during a crisis, and help prevent well-meaning but uncoordinated communications (both internally and externally).

A response plan should be the result of input from stakeholders enterprise-wide. Each of these stakeholders will ultimately have to designate someone from their group to be their lead on the team to be: (a) the person accountable for executing their portion of the plan; and (b) reporting to management.

Several well-recognized steps are involved in any response plan, and are below.

Not every data incident will involve sophisticated hackers compromising an organization’s IT systems. Physical incidents (e.g. non-electronic breaches such as departing employees taking information with them, loss of records or devices, theft of laptops) are still common. Note that an organization’s response plan should not only contemplate activation in the case of an electronic breach, but in the case of a critical non-electronic one as well.

Depending on the scope and nature of the physical data incident, it may or may not be appropriate to activate the response plan and convene the incident response team. Regardless, the first step will be to promptly investigate and take action to limit further data loss. This can be done by limiting employee and public access to the affected area and changing locks/access cards if necessary. Organizations should determine whether it is appropriate to notify law enforcement. If an internal or external investigation is being conducted, the organization will need to determine what assets have been lost/affected, obtain tracking information (if available), obtain video surveillance (if available) and, if the incident involved employee misconduct, consider HR implications of any such investigation.

If an electronic breach has occurred (e.g. a hack or other compromise of IT infrastructure that has led to data loss or exfiltration), containment is likely to be more challenging and it is more likely that an organization will need to implement its response plan and convene the breach response team. These decisions will largely turn on the size of the breach and the type of information affected.

If appropriate, the various team members should be contacted and the team assembled and briefed Communications may need to be by phone only (in some cases, new mobile phones) in order to prevent the use of a compromised email system and the risk of leaks. Secure communications, including secure phones, laptops, and networks, should also be made available to senior management and other critical employees.

Once the response plan is triggered, clear communications channels, reporting structures and accountabilities should fall into place. When deciding on these channels and structures, it will be critical to have already considered the most efficient ways to include internal and external counsel in order to preserve privilege (where appropriate).

The actual members of the team will vary depending upon the organization and the nature of the incident; however the responsibilities of team members will generally include the following areas:

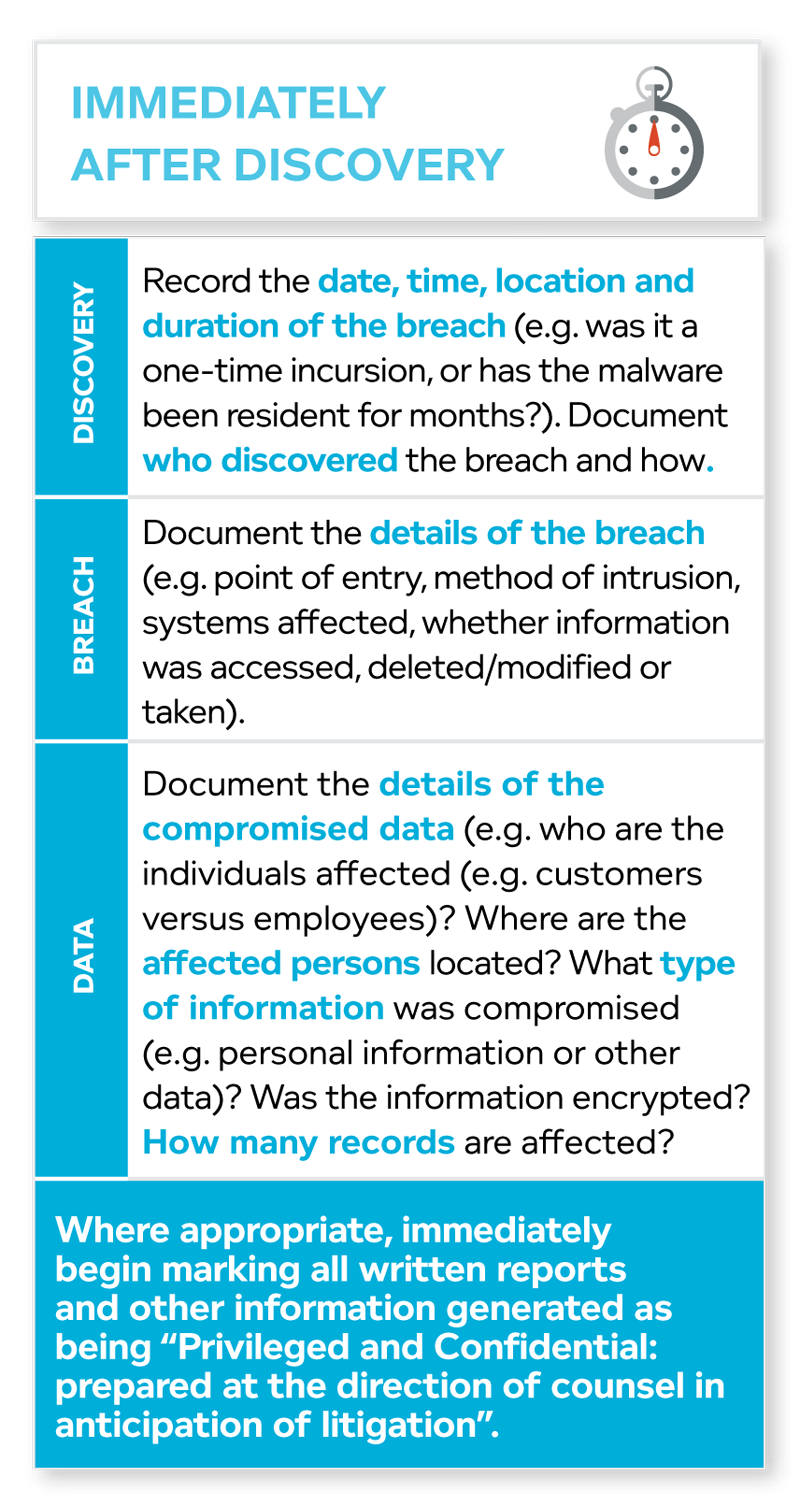

An organization should begin gathering information the moment the incident is identified. All information related to the data incident should be subject to a comprehensive litigation hold so that it can be preserved, collected and analysed at the direction of counsel (and provided to law enforcement if required/appropriate). A subsequent review by lawyers will determine what information is actually relevant to any litigation, but the first task will be identify and preserve any information that might be relevant.

As the cause of the data incident becomes apparent, and affected individuals are identified, an organization will be in a position to predict how the compromised information might be used (e.g. Was it unencrypted personal financial information that was the subject of a malicious hack? Or was it the loss of an encrypted USB key with names and addresses only? The former is much more likely to end up being sold on the internet’s black markets and used for fraud or identify theft). An organization can then begin making decisions about risk mitigation, consumer protection, law enforcement and so on.

When a data incident occurs, an organization will only have a short window of time to gather critical evidence. While the internal IT team will act as first responder to a data incident, they are often untrained in data recovery and forensic analysis and can sometimes do more harm than good, damaging critical data or inadvertently mishandling important evidence. For this reason, an outside IT forensics firm is likely to be one of the first outside vendors retained and operating after a data incident, using forensic software and protocols to perform data collection and data preservation in the wake of a data incident.

Organizations should have these relationships in place before an incident and, ideally, already have coordinated any anticipated response with their choice of external legal counsel in order to allow a seamless handoff of this critical phase during an actual incident response.

At the same time as information is being collected and preserved, and as details of the nature and scope of the incident are just becoming clearer, the organization will also need to consider (even at this early stage of its response) the medium- and long-term litigation risks arising from the incident.

It is almost certain that, in the aftermath of any significant data incident, an organization will face one, and perhaps two, kinds of class actions, be commenced against it. First, a consumer class action will almost certainly be brought on behalf of all customers potentially affected by exfiltration of personal information. Second, if an organization is a Canadian public issuer whose share price dropped immediately after the announcement of the incident, an organization may be sued by a person representing shareholders, with an allegation that the organization’s continuous public disclosure as to the state of its cybersecurity systems was misleading.

At the time of writing, no securities class action has been commenced in Canada in the wake of a data incident, but several consumer class action actions have been. Those actions have not yet been fully considered by Canadian courts and as a result, questions regarding the legal validity of the causes of action that were advanced, and the scope of possible damage awards, remain largely open.13

In Canada, a consumer or shareholder class action will almost always be brought in provincial (as opposed to federal) courts. Only one class action can proceed in each province and plaintiff’s firms generally operate on the assumption that if they are the first to issue a claim in a particular province, that discourages competing lawsuits in the same jurisdiction. Accordingly, a plaintiff’s law firms will generally issue a lawsuit in response to a data breach as soon as it can identify a suitable plaintiff who may have been affected. The statement of claim will likely have only generic wording, simply inserting the name of the organization and some basic facts about the incident. No investigation of the merits of a case will likely be undertaken before the proposed class action is issued (usually with an accompanying press release).

Generally, an organisation can expect the first lawsuit within 7- 30 days. If two months pass without a lawsuit, the chances that a lawsuit will be initiated decline dramatically (unless there is subsequent significant disclosure about the incident, such as a dramatic change in the numbers of persons affected, the type of information compromised, or supported if plausible allegations of fraud tied to the incident are revealed).

It is possible in Canada for overlapping class action to be brought in multiple provinces; as a result, an organization may need to defend multiple parallel cases at the same time. Whether one case or many, class actions tend to unfold slowly (especially where the facts are still being discovered and the law as to liability and damages is, as here, uncertain). It may be 3 to 5 years before a class action reaches trial or settlement. It is for this reason that an organization should include an outside litigation specialist on the incident response team, an involve them as soon as possible; it will be outside counsel who has their eye on the longer term consequences (e.g. asserting privilege, reviewing public messaging, and so on) while the organization and its resources are focused on the immediate response.

An organization can also expect to be the focus of regulatory proceedings principally mean an investigation by various Privacy Commissioners responding to complaints, or acting of their own accord and, depending upon the industry, could also include securities, financial institution or public health regulators, and even law enforcement agencies.

Privacy Commissioners

Organizations may be required by law to notify regulators or affected persons. The main regulators in this area will be the various provincial privacy commissioners, as well as the federal privacy commissioner. A chief concern for an organization which has suffered a data incident which includes personal information will be providing notification to the various privacy commissioners.

Currently, only Alberta and Manitoba have enacted legislation to require mandatory breach notification in the private (non-health) sector (Manitoba’s legislation is not yet in force at the time of writing). Amendments made to PIPEDA by virtue of the Digital Privacy Act now make notification of both affected persons and the federal privacy commissioner mandatory, but the relevant sections are not yet in force pending the passage of implementing regulations. In the health sector, Alberta, Ontario, Newfoundland, and New Brunswick have all enacted laws that requires mandatory breach notification.

There may be penalties for failure to report a data incident. In Alberta, the private sector mandatory notification is triggered “where a reasonable person would consider that there exists a real risk of significant harm to an individual”. Failure to notify the Alberta Privacy Commissioner of a breach that may pose a real risk of significant harm to individuals is an offence, subject to a fine of up to $10 000 for an individual and up to $100 000 for a corporation.

As a practical matter, an organization will generally want to notify all relevant privacy commissioners (regardless of whether it is mandatory), using an approach that ensures a coordinated notification process that ensures consistency of information. Organizations must be aware that while information provided to a privacy commissioner will generally be confidential, some of it may be subject to subsequent disclosure pursuant to requests made under access to information laws.

Complaints from individuals to a privacy commissioner will trigger discrete investigations aimed at resolving the matter in issue, but privacy commissioners may also initiate an investigation of their own accord into any issue within their jurisdiction. Such investigations are more likely where there are multiple individual complaints, the scope of the data incident is large or involves particularly sensitive information, where there is a larger public policy issue or need for guidance (e.g. a new type of service or business model) or where the privacy commissioner feels that consumer or public interests have not been adequately protected by the organization’s response.

Data incidents involving payment cards and/or the loss or unauthorized access to cardholder information raise special considerations in respect of the complex web of players in the chain of payment processors and the various contractual interrelationships. While there is at this time no legislative or regulatory obligation in Canada to notify payment card providers or acquiring banks of a data incident, such obligations may well arise as a result of the various contractual relationships between (and among) the merchant organization and the various bank and payment card brands in respect of the use and issuance of payment cards.

There may be a requirement to comply with sector-specific standards. The Payment Card Industry Security Standards Council was founded by leading payment card brands. Organizations accepting payment card transactions – including acquirers, service providers, and merchants – from any of these payment brands have to comply with the Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI-DSS) requirements. Although the Security Standards Council has exclusive authority to set requirements, it does not participate in compliance enforcement. The card brands themselves are responsible for enforcing compliance for all transactions conducted with their own cards. They accomplish this through policy enforcement with their member banks (acquirers). The member banks, in turn, enforce compliance with merchants. Consequently, if an organization wishes to process major credit cards, it must do so through members of the card brands, who mandate PCI-DSS compliance measures in their service contracts.

PCI-DSS requires documentation to be developed and maintained, preventive and detective security controls to be implemented, and processes to be in place in order to identify and contain any security breach attempts as soon as possible. A PCI-DSS Forensic Investigator (PFI), an IT forensics firm approved by the card brands, will conduct periodic reviews of an organization’s compliance with the PCI-DSS standards and issue reports that will recommend or decline continued certification. Non-compliant organizations are exposed to higher transaction fees imposed by their acquirer banks, contractual “penalties” imposed by the payment card brands, higher liability if a data incident occurs, and could run the risk of losing the authorization to process payment card transactions.

Additional, multiple sector-specific notifications may be required. When a data incident occurs, the compromised organization will often be required (in accordance with applicable payment card industry rules and requirements of acquirers, issuers and/or participating payment card brands) to notify their acquiring banks and/or participating payment brands, and may be contractually required to engage an approved PFI to investigate the security issue, determine root cause, and report back to affected participating payment brands and others. The PFI investigation will often be conducted alongside the organization’s own forensic IT investigation.

PCI-DSS does not provide specific guidelines on how to handle a security breach. Each payment card brand has its own policies and procedures; and they can differ among the individual brands. For example, some card brands require “immediate” notification upon confirmation of a data incident; others require notification within 24 hours of knowledge of such incident).

Some organizations may be tempted to defer or decline such reporting. However, even if organizations do not notify the bank and/or card brand network, it is very likely that these entities will independently identify the organization as a source of cardholder data compromise. Both banks and payment card networks have implemented processes to identify the source of an incident as precisely as possible.

Legal counsel should be involved in all discussions with PFI investigators and related investigations. An organization may want to consult outside counsel with expertise in this area to determine how it wishes to manage not only the PFI investigation, but its interactions with card brands, the management of its own parallel IT forensics investigation, and the preservation of privilege. This is a complex, high stakes area and the strategic management of privilege issues will be of significant benefit to the organization.

Reporting issuers are required to disclose risks in a number of disclosure documents mandated by securities laws, including in prospectuses and in continuous disclosure documents such as annual information forms. For instance, the instructions to Form 51-102F1 (Management’s Discussion & Analysis) include a discussion of risks that have affected the financial statements or are reasonably likely to affect them in the future, and risks and uncertainties that the issuer believes will materially affect its future performance.

The CSA issued its 2016 Notice updating its previous notice on the same topic, CSA Staff Notice 11-326 Cyber Security (the “2013 Notice”) for reporting issuers, registrants and regulated entities. As the CSA acknowledges, since the 2013 Notice was published, the cybersecurity landscape has evolved considerably, as cyber attacks have become more frequent, complex and costly. Citing two recent studies, the CSA noted in its 2016 Notice that:

In the 2016 Notice, the CSA first provides a summary of its recent initiatives to monitor and address cyber security risks in order to improve overall resilience in our markets. For example, noting the failure of many issuers to fully disclose their exposure to cyber risks, the 2016 Notice states that CSA members intend to re-examine the disclosure of some of the larger issuers in the coming months and, where appropriate, will contact issuers to get a better understanding of their assessment of the materiality of cyber security risks and cyber attacks. The CSA also notes current initiatives on enhancing cross-border information sharing among regulators related to cybersecurity.

The 2016 Notice also provides links and references to a number of particularly helpful cybersecurity resources that have been published by various financial services regulatory authorities and standard-setting bodies in an effort to improve the preparedness of market participants to deal with cyber incidents. Such resources include:

As noted above, the SEC has provided similar guidance related to cybersecurity risk disclosure. While risk factor disclosure is entity specific, in its CF Disclosure Guidance: Topic No. 2 – Cybersecurity, the SEC noted that, depending on an issuer’s specific facts and circumstances and the level of materiality, cybersecurity risk factor disclosure include the following: (i) aspects of the registrant’s business or operations that give rise to material cybersecurity risks and the potential costs and consequences; (ii) To the extent that functions that have material cybersecurity risks are outsourced, a description of those functions and how those risks are addressed by the issuer; (iii) a description of cyber incidents experienced by the issuer that are individually, or in the aggregate, material, including a description of the costs and other consequences; (iv) risks related to cyber incidents that may remain undetected for an extended period; and (v) any relevant insurance coverage.19 In its guidance, the SEC noted that while entity-specific disclosure should be provided, securities laws do not require disclosure that would result in compromising the issuer’s security. Rather, the aim is to provide sufficient disclosure to allow investors to appreciate the nature of the risks faced by the issuer without compromising its security.

In addition, issuers may need to disclose known or actual cyber incidents, to provide context and investors and costs and other consequences in order to allow investors to appreciate the nature of the risks. As well, if a cybersecurity incident constitutes a material change, a press release will need to be disseminated and filed and a material change report will need be filed.

Does the organization have cybersecurity risk insurance? If so, is the incident covered and to what extent? Agreements and policies will need to be reviewed to make these determinations. As well, insurance agreements generally have a requirement that the insured promptly notify the insurer of a suspected incident – organizations will want to make sure they know when such an obligation is triggered, how long they have to report, and what information is required.

Once the above is complete, the insurer should be notified, but only once counsel has been involved and approved.

Where a third party (such as an IT service provider) is implicated in a loss of data, relevant agreements should be reviewed for indemnification clauses and any notification or informational requirements therein. Once the above assessment is complete, the third party service provider should be notified if appropriate, but only once counsel has been involved and approved.

Employee liability and/or responsibility may also be in issue. A review should be conducted to determine if corporate policies were followed or if laws were violated. Appropriate actions should be taken. If the organization has a unionized environment, labour considerations may also be in play.

Law enforcement may become involved. Such involvement can occur in two ways, either by law enforcement approaching the organization with a request for information or by the organization itself approaching law enforcement with a request that law enforcement get involved.

Organizations should be aware of disclosure restrictions, especially regarding personal information. If approached by law enforcement, an organization should be aware that it is only entitled to disclose personal information to law enforcement without the consent of the affected individual where it is required to do so pursuant to a warrant or summons, or as otherwise authorized by law. Whether or when an organization may disclose personal information requested by law enforcement, but not required by law, is a complex and evolving area given Supreme Court jurisprudence in this area.

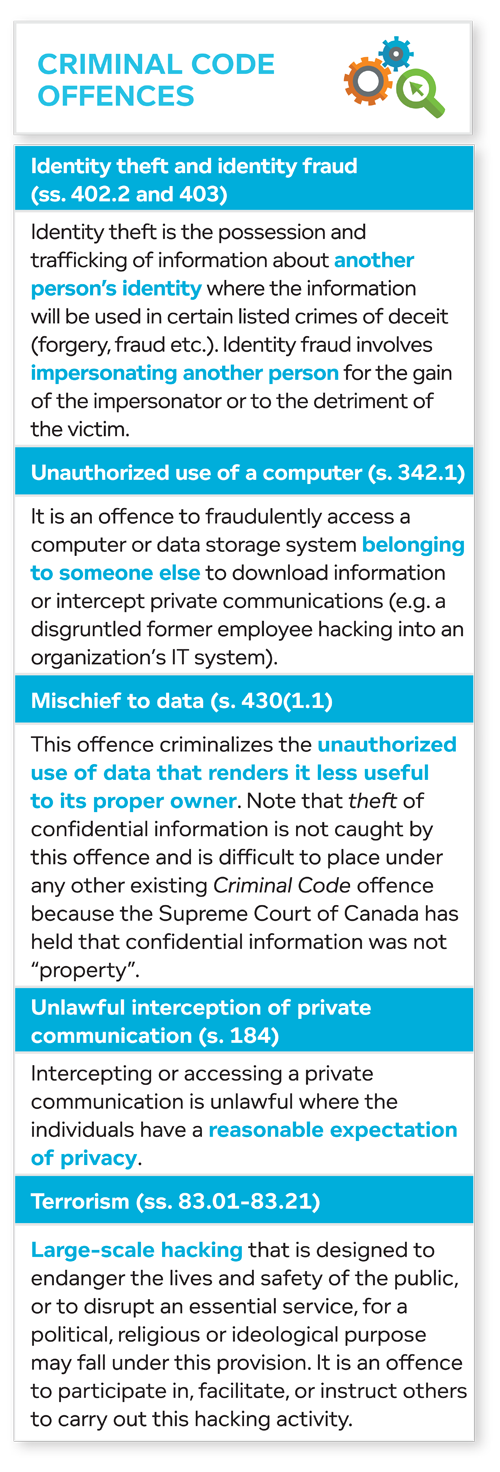

Law enforcement may also be involved because the organization has concluded it is the victim of a criminal offence (see sidebar).

Once law enforcement is involved, they may request that breach notifications and other disclosures be delayed in order to preserve the integrity of their investigation, or they may otherwise prohibit the release of certain information. This may conflict with the organization’s existing statutory or contractual obligations and, accordingly, legal counsel should be involved in all discussions with law enforcement.

One of the most significant stakeholder groups in a data incident is an organization’s customers. Canadian consumers have high expectations that not only will they be promptly notified about a data incident but that organizations will take immediate, clear steps to protect consumers (or allow consumers to take steps to protect themselves). The gap between what organizations do, and what consumers expect them to do, creates an area of risk.

Among other things, organizations should consider establishing a call centre to address consumer concerns. In addition, consumers often expect organizations involved in significant data incidents involving payment cards or identifying information to offer credit monitoring and/or identity theft monitoring.

A well thought-out and robust customer response can, in addition to helping retain customers and preserve brand value, have a significant impact on potential class actions fees and damages.20

In the case of most large data breaches, a decision will be made to activate a call centre (as opposed to dealing with customers using internal resources on an ad hoc basis).The sooner a call centre is up and running, the sooner an organization can begin managing the message, limiting reputational risk and litigation risk.

There are typically two main types of protection products that are offered: credit protection and identity theft protection. Credit protection involves no-cost credit monitoring for customers and alerts customers if there is activity or something new on a customer’s credit report. Identity theft protection involves monitoring driver’s licence, social insurance number and other foundational identity documents and online activity to see if any personal information is being bought or sold online, and monitoring court records and other markers of possible identity fraud.

These protection products may not be required in all cases. An organization affected by a data incident will need to consider carefully what products it will offer and, if it decides not to offer certain products, understand that the decision will come under significant scrutiny, particularly if it later emerges that such protection may have been warranted. The provision of such services also assists in mitigating possible damage, which will be a factor in any subsequent litigation.

Note that there are significant differences in the protection products that are available in the United States versus Canada. Where a data incident affects both jurisdictions, companies should expect to receive inquiries as to why better/longer/more complete services are being offered in one jurisdiction as opposed to another. These inquiries can be reduced if the nature of the products being provided is not detailed in public statements, but rather such statements mention only the fact of such products being made available.

In some cases, fraud protection or identity theft monitoring may not be appropriate or feasible. In other cases, consumer goodwill may be at stake. In such circumstances, an organization may want to consider compensation. Ideally, this will have been explored well in advance of any data incident, and an organization will have a clear understanding of the form of such compensation, its distribution, the amount, and so on (e.g. $10 gift cards to all consumers who present evidence of a purchase between qualifying dates).

Data incidents at major retailers, government departments and financial services organizations should serve as a clear warning to organisations doing business in Canada that collect, use and/or disclose personal information. Consumers actively expect that these entities should take market-leading steps to protect personal and financial data.

Increasingly, good information management practices go beyond matters of privacy. Malicious hacks (from outside and from within) and ransomware demands have targeted intellectual property, trade secrets and other critical business information with noticeable impacts on share prices, director and Board longevity, and industry competitiveness. Clients need support from counsel who can marry legislative compliance and the application of industry codes of conduct and privacy policies in various jurisdictions with a practical knowledge of commercial and technology outcomes - all in a manner that will help a client preserve privilege.

Cybersecurity, protection of business information and data, and strategic management of the production and/or retention of information are all significant aspects of our practice. Our privacy and data management lawyers offer perspective on all aspects of information management, storage and transfer. Mitigating risk for clients is always our first priority and we have helped clients manage the entire lifecycle of data, including providing guidance to companies looking to prepare for and prevent a critical data incident. When crisis occurs, we draw from a team of leading class action litigators and subject matter specialists who have responded to some of the highest profile data incidents in North America and are involved in many of the key cybersecurity initiatives (both private and public) in Canada.

For more information please contact:

Dan Glover

416-601-7713

dglover@mccarthy.ca

Christine Ing

416-601-7713

christineing@mccarthy.ca

Barry Sookman

416-601-7649

bsookman@mccarthy.ca

A special thanks to Death.